They’re siblings, not twins.

It pays to be prepared for the differences between the two islands when you venture across Cook Strait – particularly if you’re a pilot who flies mostly in one or the other island.

So what are the main things to look out for?

Weather

It might sound like stating the bleedin’ obvious, but let’s get right back to basics and talk about the weather. Not just wind, but also precipitation, including fog, snow, rain, and drizzle.

“With the weather, nothing is hard and fast. There are many dynamics and variables affecting how the weather behaves,” says CAA Aviation Safety Advisor, and A-cat instructor, Carlton Campbell.

One of those variables is terrain, particularly mountain ranges.

While the North Island is dominated by its unique volcanic plateau and has its share of mountainous ranges, nothing compares to the dramatic Southern Alps. They’re a massive obstacle for prevailing winds laden with moisture from the surrounding oceans.

Wind patterns and terrain

Wind of some sort is often present in a mountainous area.

Let’s start with what happens in a westerly, New Zealand’s prevailing wind.

“In the South Island, that means low cloud and rain in the west, and windy, turbulent conditions in the east,” Carlton says.

Why? It’s all about orographic lift – when a moist, moving air mass meets a geographical feature, such as a mountain range, the air mass needs to rise up and over it.

When the air reaches dew point, clouds form, and, possibly, rain. Therefore, the windward slopes of a mountain range tend to have higher rainfall than the leeward slopes. And the leeward side has more air turbulence.

Carlton compares the orographic effect to a river flowing.

“When a river meets protruding boulders and stones, the water flows over and around them, and we see disturbance in the water on the downstream side of the stones. That’s like when wind meets hills – there’s turbulence on the lee side because the air slows down as it passes over and around the obstacle.

“When a river meets a bigger obstacle, such as a weir, the water needs to flow up and over that barrier. The water on the downstream side of the weir gets churned up as the river crashes down to find the riverbed again.

“That’s what happens when a westerly comes over the Southern Alps. It goes up, over, and down the other side, creating a great deal of turbulence in the lee of the mountains.”

Penny Mackay, a Nelson-based pilot, A-cat instructor, and flight examiner, says Kaikōura and the Canterbury and Otago areas can be particularly nasty in a westerly. She explains that the opposite effect occurs with an easterly.

“For a lot of the east coast, an easterly will tend to bring low cloud, reduced visibility, and various forms of precipitation. There’ll be turbulence in the west.”

Rochelle Fleming, a pilot, B-cat instructor, and meteorologist based in Taranaki, says similar effects occur in North Island terrain, but to a lesser degree.

Key points

- Look for signs of orographic lift, such as cloud formations over mountains.

- Anticipate turbulence, even if it’s not forecast.

- Plan routes avoiding the leeward side of mountains where turbulence and downdraughts are stronger, particularly when winds are more than 15 knots.

Wind flowing across mountainous terrain often induces cloud formation. Photo courtesy of Penny Mackay.

Mountain waves

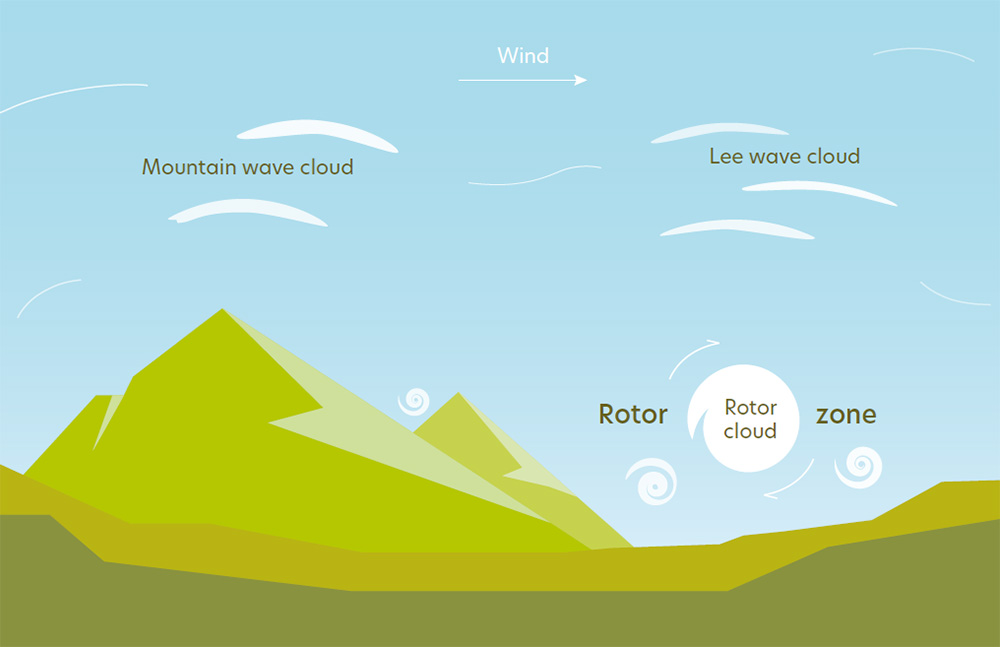

Mountain waves are another consideration. You may encounter them when flying near or over mountainous terrain. They occur when strong, stable winds blow over the mountains and the air descends on the other side, creating a wave pattern in the atmosphere.

The South Island nor’wester is the classic situation, but pilots need to consider other wind directions, too, and even relatively small mountain ranges can still form significant mountain waves. For example, a southwesterly can form mountain waves off the ranges at the top of the South Island, and these waves can extend right across the lower North Island.

Mountain waves can extend vertically and horizontally for great distances and they can produce notable effects, such as:

- severe turbulence on the leeward side

- turbulent, rolling rotor clouds can form beneath the main wave, indicating strong, rotating air currents

- lenticular (lens-shaped) clouds can form at the crest of the waves, and stay stationary despite high winds. They’re a visible indication of high upper winds, and therefore the potential for low-level rotor clouds.

Katabatic and anabatic winds

It’s important for pilots to understand the effects of these winds when flying in and around mountain ranges. Anabatic winds occur during the day as the sun heats the slopes of mountains or hills, causing the warm air to rise and create strong updraughts. Lake or sea breezes will strengthen anabatic winds.

As the air cools when it rises, the moisture content increases to create convective clouds looking like stacks of cotton-wool balls. If the air becomes more unstable, cumulonimbus clouds may form, resulting in rain and, sometimes, thunderstorms. Turbulence and poor visibility can occur, meaning you’ll need to adjust your VFR flight path to maintain safe distances from the clouds.

As the sun sets and the slope cools, the air in contact with the slope slows down and stops rising. It starts to flow downslope, forming a katabatic wind (sometimes called ‘mountain flow’). This transition can happen quickly in the evening or as the sun is blocked by terrain, particularly if the temperature around the tops is colder from snow cover.

Katabatic winds are usually stronger than anabatic in the valley floor, unless the anabatic is strengthened by sea or lake breeze.

Carlton says if winds are light and no prevailing upper winds are evident, the most prevailing conditions lower in a valley will be katabatic wind, due to colder air around the tops draining down the valley.

The transition from anabatic to katabatic wind can create localised turbulence and a rapid drop in temperature.

Penny Mackay agrees that the effects of the Southern Alps on the weather in the South Island are immense.

“They’re a magnet for moisture and a funnel for wind.

“Because of the height of the mountains, VFR flight often occurs below the mountain peaks and in valleys, where these effects are generally greater.”

She adds that the venturi effect – when air is forced through mountain passes – it can cause strong gusts – another factor for pilots to keep in mind.

James Churchward, an A-cat instructor and flight examiner at Tauranga Aero Club, says the various weather effects in and around the Southern Alps can be a big learning curve for North Island pilots when they head south for fly-aways and competitions.

“While these weather effects do happen in the North Island, pilots travelling south need to consider the effects of the wind being forced over much larger mountains and terrain.”

Key points

- Be aware of the time of day and local terrain to anticipate the effects of anabatic and katabatic winds.

- Be prepared for turbulence and changing wind patterns.

Typical mountain wave and associated turbulence. Source: CAA

Typical fronts

Flying in conditions where high- and low-pressure systems meet – especially when it produces a cold front – can present challenges for aviators unaccustomed to flying in the South Island.

Penny says pilots should expect southerly fronts to be much more intense in the South Island.

“It’s easy to underestimate how fast a front travels and the cumulus grows, sometimes with associated heavy rain showers in these fronts. I’ve had students caught VFR in IMC inadvertently, trying to outclimb a growing cumulus.”

Carlton explains that the passage of a southerly cold front through the South Island is relatively steady. It can get caught up in the mountains, but then the front typically escalates across the Canterbury Plains where there are few obstacles in its path.

By comparison, “Northerlies in the South Island often bring layered cloud formations which can be quite benign. But if there’s enough moisture in the air, the cloud layers can close together and bring reduced visibility for extended periods of time,” Carlton says.

This effect can have dramatic localised impacts. To illustrate a typical nor’easter in the top of the South Island, Penny recalls a group of students and instructors contacting her by phone from Karamea, in the upper South Island, as they tried to head north.

Despite having received advice that it wasn’t a good idea to continue because of bad weather approaching, they’d decided – based on their North Island flying experience – to continue to fly low-level around the coast to Motueka.

“It was a nor’easter at the time. In the North Island, pilots can often fly around under a 1500ft stable layer of cloud, knowing it will often stay like that. But in the top of the South, a nor’easter can sit out in the bay and then suddenly move in. Visibility can go from 1000ft to fog at ground level very quickly.

“The group eventually made it to Motueka – the last section in very poor visibility and drizzle. As the last one landed, the cloud came down to the ground.

“They were all extremely thankful to have landed safely.”

Key points

- A front marks a change in weather conditions, which may be rapid, especially if it’s a fast-moving cold front.

- Warm frontal conditions of low cloud and precipitation can last for extended periods of time before clearing.

Flying in the North Island

“South Islanders shouldn’t underestimate North Island weather – it can, and does, catch pilots out,” says Rochelle Fleming.

While the North Island doesn’t have the dramatic effects of the Southern Alps, it has its fair share of mountainous terrain and, importantly, its unique volcanic plains.

Rochelle says this means the North Island isn’t exempt from the unexpected impacts of terrain, and pilots more accustomed to flying in the South Island need to be aware of that.

Penny says that while the South Island has a relatively thin coastal strip (because of the Southern Alps), the North Island has a lot of terrain between the coast and the main ranges, from the Tararua Range to the East Cape.

“This creates less predictable turbulence, particularly if you’re flying west to east, or vice versa (the orographic effect). Turbulence forms off all the hills and ranges, so you can be exposed to it for a lot longer than you might expect.

“There’s a lot of rugged terrain north of Palmerston North, so regardless of wind direction, pilots need to consider the best route to fly on any particular day.

“Even on a benign, okay-looking day, a deck of stratocumulus cloud between Whanganui and Te Kūiti can leave not much terrain clearance to climb above turbulence. For example, a Graphical Aviation Forecast (GRAFOR) might show BKN 2500ft, but that will be sitting on or close to the ridge tops, making an already difficult area to navigate a real challenge.”

Flying around volcanoes

Rochelle says Mt Taranaki (a cone volcano) can catch out both South and North Island pilots in windy conditions.

The orographic effect can lead to strong, localised turbulence. The leeside can experience turbulent eddies and wind shear, which can be hazardous for pilots. These effects, Rochelle says, can be unpredictable and greater than you would normally expect in the lee of a mountain. The effects can continue for some distance downwind.

Similar effects occur in and around the North Island’s other cone volcanoes, including Mts Ruapehu, Tongariro and Ngāuruhoe. And don’t forget, the North Island’s volcanoes are often active. Keep an eye on NOTAMs and consider downloading the GeoNet app.

Key points

- Each volcano is a massive obstacle to wind, with degrees of lee turbulence relative to wind strength.

Cloud in the North Island

While both islands will experience fair-weather cumulus clouds, Rochelle says South Islanders can be surprised by the extent such cloud can cover inland parts of the North Island, often with a flattish base and described on GRAFORs as Cu/Sc.

“This can be just above the hill tops and, while usually not particularly turbulent, the bumpiness can be enough to make it an unpleasant ride for your passengers when flying between Whanganui and Te Kūiti, for example.”

Surprises in the Tararua Range

The Tararua Range has some surprises for itinerant pilots, especially in a westerly, Penny Mackay says.

“The turbulence can be especially vicious, with the meeting of the downdraughts off the mountain wave on the Wairarapa side and the venturi effect coming through Cook Strait in a westerly.

“This can produce much worse effects than you would normally expect in the leeside of the Tararua Range in the Wairarapa.”

Penny recalls a friend whose twin-engine aircraft ended up with cracked engine mounts from the unexpectedly severe turbulence in the Wairarapa area because of exactly those weather conditions.

“Rotor from wave conditions in this area has also led to the break-up of a glider in the past,” she says.

Cold fronts

Rochelle says that while cold fronts can stall across the North Island, and sometimes may be so weak they can be dropped from the weather charts, there’ll still be leftover low-level moisture, which can cause unexpected drizzle and low cloud, especially on the west coast.

“Recently, an experienced pilot encountered just this situation travelling along the coast between New Plymouth and Raglan, where an old, weak front lingered.

“At the end of a long day, with the temperature dropping and short winter daylight hours, fog started to form on the coastal hills as a light westerly pushed moisture onshore.

“At about 800ft above ground level, just short of Kāwhia, and conditions looking to be deteriorating ahead, the pilot made the wise decision to head back to New Plymouth for an enjoyable evening.”

More information

GAP booklet: Mountain Flying [PDF 1.5 MB]