A routine flight from Paraparaumu to Tākaka in November 2024 turns into a dramatic sea ditching.

Landing at Paraparaumu aerodrome to drop family members home after their visit to Golden Bay, Laurence (not his real name) waved them off, stowed their life jackets away and completed his preflight checks for the return journey.

All was well.

With winds of eight knots at 320 degrees and minimal cloud, Laurence climbed to 5000ft north of Cape Jackson, adjusting course to avoid cloud and turbulence.

With an outside air temperature of 5 degrees, Laurence used carb heat every few minutes, checking temperatures and pressures regularly. The engine was leaned appropriately.

Once clear of the turbulence, Laurence continued to use carb heat at regular intervals. The steady head wind had his ground speed at 75-80 knots, increasing to 90 knots in the second half of the flight, and the fuel was looking good.

He had been back in cruise for about 15 minutes when he used carb heat and noticed a 200 RPM drop.

“I left the carb heat on for longer than usual to make sure carb icing was not an issue. With the carb temperature at about positive 20 degrees, the RPM stayed stable and there was no sign of rough running or increasing RPM. The conditions were a steady 25 knots north-westerly, with high cloud.”

Everything went quiet

“Then, as I closed the carb heat, the engine instantly popped, banged, and died. The prop was windmilling. I immediately applied carb heat hot, and full throttle, full mixture, and I swapped fuel tanks.

“The engine restarted and returned to 2000 RPM. I immediately adjusted the mixture while altering my course to run better with the wind and more towards land. I tried to climb.

“After this, the engine RPM never got above 2000 and felt like it was surging and not producing full power. This phase lasted about 10 seconds, during which I called Nelson Tower, identified myself, said I was having engine issues and to stand by.

“After a short period trying various engine configurations, I got approximately 10-20 seconds or so at 2000 RPM.

“I was still trying to use that power to climb and I believe I gained about 350ft. That’s when I made a Mayday call. The controller said they had me identified and asked for aircraft colour and persons on board.

“Once the engine died – I believe I was at about 3000ft – I trimmed the aircraft for 70 knots (best glide). The prop continued to windmill for about 30 to 45 seconds, or the first 500-800ft of glide. Then the prop stopped windmilling, and I made a radio call that I was going down.

“Everything went quiet. Like if you switch your car engine off while doing 100kph. The only sound was the wind passing over the plane.

“I set off my SOS satellite communicator and clipped it to the top of my life jacket. I opened my door and moved everything around me away. Then I grabbed my phone.

“At around 2000ft, the prop still wasn’t moving.

“I went through the starting procedure for the engine – master on, primer locked, throttle and mixture set. I pressed the starter button. The prop did not move at all. I believed I could hear a clunk, like the starter engaging but not being able to spin the prop.”

You’re bloody plummeting!

“I checked my phone. My partner had messaged asking, ‘All good?’ She was watching Flightradar24 for my timing and saw I had adjusted course. I replied with ‘Engine failure, called services, swimming soon’.

“Her reply? ‘You’re bloody plummeting, are you joking??’

“I pushed and tried the starter motor for the final couple of minutes of the glide, but I never saw the prop move from where it stopped originally.

“I did my final checks – SOS device still attached, door still open, headset removed. My last communication with Nelson Tower was to ask how long I would be waiting for, but at that stage they couldn’t guess.

“In the last minute or so before impact, I continued my glide with the wind until I was about 100-200ft above water.

“I then turned into the wind to reduce my ground speed and got as low as I could, intending to stall the aircraft into the water at the point of contact.

“As I got within 20-50ft, I pointed the plane parallel to the waves so I could touch down crosswind, along the troughs between them.

“I braced my feet solidly on the rudder pedals, phone in my right hand and controls in both hands.

“Consistent with the electronic flight bag on my phone, I believe the approach speed shortly before impact was about 32-42 knots. I tried to get as slow as possible before contact with the water, and a final flare for as long as possible.”

A solid wall of water hit me

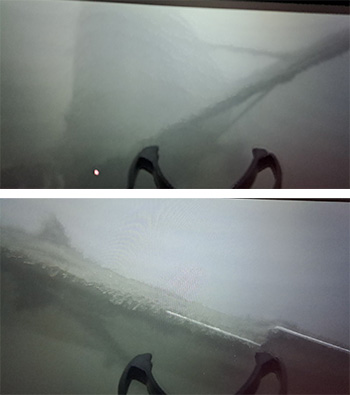

Photos supplied by pilot, ‘Laurence’.

“I thought hitting the water would be okay, but it was quite an impact.

“The main wheels hit first and immediately dug in. The nose plunged into the water, the windscreen imploded and a solid wall of water hit me.

“I must have taken a good breath, and I found myself with my eyes open underwater. At the time I didn’t know I was upside down – I was disorientated.

“My biggest priority was to get the hell out of there and I was confident I could do it. I could see the door handle I had opened.

“But I was a bit anxious…

“I pushed off the cabin wall towards the door, and made my way through it, careful not to be snagged. My life jacket inflated during this process. In a few seconds, I was out.

“Immediately after getting out of the plane, I was standing on the wing of the upside-down aircraft. I climbed up the belly to the highest point on the tail. Along the way, I got my boot caught in the flaps. It was a reminder to make sure I didn’t get caught up with the aircraft as it sank.

“The nose remained the lowest point, and the tail pointed into the air. I had hoped I could sit on the tail as she floated for a while, but this was short-lived. The plane was steadily sinking, and within about four to six minutes, it was entirely under water.

“Throughout this, I managed to hold on to my phone. My phone dialled 111 automatically on impact, but I could not get a steady line for other calls.

“I got a couple of texts out to my partner saying, I was in the water but I was okay.”

I could hear each one coming

Aircraft before salvage. Photo supplied by pilot, ‘Laurence’.

“My plan now was to keep as warm as I could, stay floating and focus on the first 20 minutes. I don’t like swimming on the best of days.

“I was on my back, and I began kicking and heading backwards into the waves, so I would have less water over my face.

“I was hoping rescue services would get an updated position from my SOS device.

“I’ve spent some time at sea, and I estimate the swell and chop was 1.5 metres with breaking whitecaps. Later, I found this aligned with the views of the harbourmaster and coastguard.

“The wind was 15-20 knots. Every couple of minutes a wave would crash over my head, covering my face with water.

“I could hear each one coming, which gave me a warning to sneak a breath in. Towards the end of the hour I was in the water, I believe the wind was decreasing. This ties in with the sun setting and the reported 10 knots from the pilot of the rescue helicopter.

“The first 20 minutes rolled into the next. I was starting to cool down, and I fought the urge to stop kicking1.

“I reached back behind my head to ensure the satellite communicator was still attached, but instead found some material. It was a spray hood with a clear screen, which was part of my life jacket.

“I pulled this over my head and it covered my face. I tucked my arms inside it.

“This was great for two reasons – I had less water over my face from the whitecaps, and it had a bright hi-vis strip with reflectors that I could wave around once the helicopter was nearby. As required by Part 91, I also had a water-activated light attached to my life jacket.

“My game plan remained the same, keep kicking to stay warm and open the hood intermittently to hear or see the helicopter.”

Feeling extremely small

“After about 50 minutes in the water I was cold, but I saw the Nelson Marlborough rescue helicopter heading straight at me from the expected direction.

“I lifted the hood and waved it around. I was confident they were right on the money and had me in sight, but I soon felt extremely small in between the whitecaps and swell.

“The helicopter nearly went right over me. They made a left turn after about half a mile and began their grid search. I continued my plan of waving with the spray hood and kicking.

“While the rescue helicopter was searching, I looked up to see what I thought was a commercial jet doing low passes. I now know it was the air force looking for me.”

“After another three or four passes in about 10 minutes, the rescue helicopter descended and turned to me.”

“You’re welcome”

“I was massively relieved, but also hypothermic, and I can’t be certain of my recollections and specific details after that.

“My memory is that the helicopter hovered just downwind of me, and a crew member was lowered down on the winch.

“She entered the water and swam towards me. I thanked her for coming, and she replied, ‘You’re welcome’. I asked if I could hold on to her and she said, ‘Of course’.”

Sinking like a stone

“She [the helicopter crew member] entered the water and swam towards me. I thanked her for coming, and she replied, ‘You’re welcome’.” Photo courtesy of Nelson-Marlborough Rescue Helicopter Trust.

“There was a bit of a struggle to get the sling over my life jacket. The crew member deflated my life jacket, and this let the sling secure me fully.

“However, without the buoyancy of the life jacket, I sank like a stone and was a complete dead weight for the crew member.

“I was still locked on to her but there was slack in the winch rope. I took a good breath and did my best not to drag her under.

“She was extremely competent and remained holding me afloat even with me pulling her down. After a couple of minutes of this, the crew member gave a thumbs up to the helicopter above us.

“The helicopter was 75-100 feet away and the winch was slack, but then the helicopter moved towards us and the winch pulled us up out of the water.

“We got up to the skid and I fell into the floor of the helicopter. I eventually got up and onto a seat. From here my memory gets very fuzzy. I don’t remember much of the flight.”

Butt-naked atop the hospital

The helicopter landed at Nelson Hospital around 9pm. Laurence thanked the crew and climbed out of the aircraft.

He says the hospital team that met him off the helicopter were “phenomenal”. They helped him out of his wet clothes, and – despite feeling exposed due to his “butt-nakedness on top of the hospital” – he says he was “unbelievably” grateful for their care and expertise.

As the hypothermia set in, he convulsed in his hospital bed as a medical team put on his oxygen mask.

But, remarkably, apart from some bruising on his lungs, Laurence was uninjured in his extraordinary ordeal.

What Laurence learned

“Engine management and attempting to start turned out to be futile, but when the issues occurred there was no panic because I followed the basic steps. I believe running through these steps consistently while flying makes this an automatic action.

“It’s important to immediately talk to a station that’s monitored, so your emergency call is heard, identified and received. Once I did this, I knew help would be coming. This gave me the hope I needed to make the next part easier.

“I recommend you explore your SOS device on the couch at home, so using it becomes a logical, easy process and doesn’t induce panic. The SOS device was unbelievable, once I set it off.

“The satellite communicator’s response team kept my father and partner constantly updated with detailed information. I will factor this device in for life.

“My life jacket was one of the key reasons I survived the incident. The spray hood was a lifesaving feature, by stopping water splashing my face and having hi-vis strips that helped the helicopter crew spot me.

“I also put a water-activated strobe light on the life jacket, which would have been good if the rescue had to continue after dark.

“I always fly with the life jacket crotch straps clipped in when flying over water. This is a small step on the ground, but it would be very difficult to do if gliding into the water.

“I’m unsure of the true science behind remaining in a ball in the water versus kicking my legs, but if I had to do it again, I would choose to kick.

“I believe this had two benefits – it kept my heart rate, blood pressure and core temperature up. It also gave me a mission to complete as I was aimed at the closest shore, about seven miles away.

“I knew I wouldn’t get there due to the swell and waves, but it also kept me closer to the initial impact and last reading of the plane’s emergency locator transmitter (ELT).

“Having a plan, with steps I could influence, was another key in my head. Remaining logical was a top priority – I didn’t feel particularly panicked.

“I had a few steps to follow, and I focused on them – get the plane down as softly as possible, get out and free from the aircraft, stay afloat, and stay warm (have a mission, kick, and look for the helicopter).

“I grabbed my phone before I ditched, because another form of communication would be useful, and I could still grab the controls for impact.”

What Laurence would do differently

“I had three other life jackets in the plane, but two were in the baggage compartment. Ideally, I would have kept these in the back seat and grabbed them before the impact.

“If my life jacket had not worked or had torn, having spares would have saved my life. I would have struggled to float without a life jacket.

“My phone dialled 111 automatically on impact. That was great, but the call kept dropping off and I couldn’t answer incoming calls because I couldn’t slide the wet screen to pick up the calls.

“A waterproof marine radio clipped to the life jacket would have been more useful – I would have had updated information on what was unfolding at their end, and how long I had to be in the water. And a diving ‘safety sausage’ would have made it easier for rescuers to see me.”

Laurence didn’t update his ELT details with the Rescue Coordination Centre when he bought the plane.

“This meant one extra step for the RCCNZ, as they had to call the listed previous owner and get my information. That meant a delay I could well have done without!”

The engine

Laurence’s aircraft has since been salvaged and the engine is awaiting examination. Vector will bring you up-to-date in a future issue if the cause of engine failure can ever be determined.

Now read

GAP booklet: Survival [PDF 8.4 MB]

Footnotes

1 CAA and FAA medical advice is that it’s best to stay in a foetal position to conserve body heat.

Main photo iStock.com/Jim Lin