By Marc Brogan,

CAA Chief Advisor of Standards

Your awareness of your place in the air is vital. So what conditions limiting that awareness should you always be aware of?

Despite advances in technology, improved pilot training, a greater understanding of human factors, and enhanced aircraft design – one problem remains the same in New Zealand’s skies.

Aircraft continue to be drawn, almost magnetically, toward each other – at best, giving both pilots and their passengers a nasty fright, and at worst, involving them in a mid-air collision.

In New Zealand since 2008, there have been three fatal mid-airs at unattended aerodromes, resulting in seven deaths. There continue to be a significant number of ‘near‑miss’ events. Between 2018 and July 2023 there were 337 (see table), 158 of which have required avoiding action.

They’re a sobering reminder of the human frailties we take into the air every time we pilot an aircraft. A single decision, or a single action or non-action that damages our lookout, can be the difference between a safe flight and tragedy.

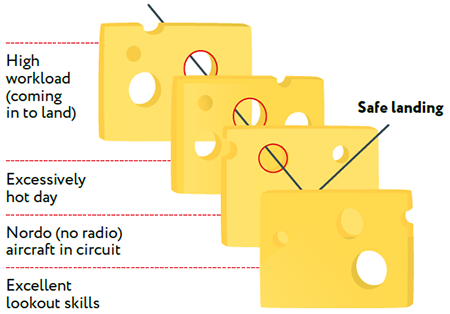

When factors such as high workload, poor radio calls, perhaps the sun at an awkward angle, drive us toward catastrophe, great situational awareness1 and great lookout will provide that last slice of swiss cheese preventing an accident.

Number of reported ‘events’ in New Zealand 2018 – July 2023

| Year | Air proximity | Loss of separation | Near collision | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 32 | 13 | 9 | 54 |

| 2019 | 28 | 12 | 13 | 53 |

| 2020 | 17 | 29 | 14 | 60 |

| 2021 | 18 | 32 | 16 | 66 |

| 2022 | 20 | 22 | 14 | 56 |

| To July 2023 | 26 | 15 | 7 | 48 |

CAA research into mid-air collisions has found many of those tragedies shared a number of features.

The Licensing and Standards team found the most marked feature the three most recent mid-air collisions had in common was that they all happened at their home aerodromes, that were all unattended.

The ‘swiss cheese’ model of accident causation

Pilots’ lookout and situational awareness can be the last slice of cheese, where the holes don’t line up, preventing a catastrophe.

The findings of the research into those three mid-air collisions are described here, because some of the factors common to those three accidents could also be part of your next flight.

Will you be prepared for them? Or will you be surprised by them, allowing them to impair your lookout and situational awareness?

Common factors in the accidents

In 2008, three people died in a collision between a C152 and an R22 at Paraparaumu.

Two years later in Feilding, two died in a collision between two C152s.

And in 2019, a collision in Masterton between a C185 and a Tecnam P2002 killed another two.

All three collisions were at aerodromes subject to high itinerant use, and local traffic, all on the same frequency. Was radio congestion a factor?

This reminds us that while the radio is a great tool for situational awareness, lookout is key.

As already noted, all the accident aircraft were at their home base.

Was there, as a consequence, an over-reliance on local procedures – ‘overhead water tower’ type calls – that itinerant traffic would not understand?

Did complacency play a part? It’s easy to take your eye off the ball when it’s your home aerodrome, but this has been the precursor to many incidents and accidents.

The reports from the Transport Accident Investigation Commission on these accidents indicate they all occurred when the pilots were undertaking degrees of non-standard practice. It was noted in the TAIC report findings and recommendations that the pilot training content and syllabus should be reviewed, especially regarding lookout and standard procedures.

That shift from a standard and commonly understood procedure or method will have resulted in a loss of predictability for other pilots. ‘Shared airspace’, particularly at unattended aerodromes, absolutely means a shared understanding of procedures.

There were no weather-related factors in the accidents – all occurred on clear VFR days with no cloud.

But keep in mind that time of day, and the position of the sun, are often factors in incidents – the pure difficulty of ‘seeing’ – especially on an anti-cyclonic day with lots of haze.

Be aware of long flying days that can lead to physical tiredness, and all the potentially poor decisions associated with that. Remember the I’M SAFE check for yourself before flying.

Between, and within, the six aircraft involved in the three accidents, there was significant difference in crew experience and gradient.

In Paraparaumu, one flight was a PPL test and one was an early solo training flight.

The Feilding accident involved an aircraft doing a training exercise – where a dual training flight was practising overhead joins at lower than standard height – while another aircraft climbed out after take-off.

In Masterton, a new commercial pilot operating a complex aircraft type was descending to land, while a newly qualified pilot was established on long final.

All the flights therefore contained psychological stressors that could have possibly influenced pilot performance.

For various reasons, all the pilots were under physiological stress. Some were flying on a hot day. All had high workload during a hectic phase of flight, approaching to land. Some were handling a complex aircraft type. All of them had either pitch, bank, or both – and would have been experiencing ‘G’ as a consequence – just before the accident.

And all would have been trying to see and identify conflicting traffic.

iStock.com/customphotographydesigns

‘G’ and other significant physiological factors

Consider, if seeing and identifying other aircraft is already challenging because our body is experiencing ‘G’, and possibly, the other effects described here, what mental capacity do we have for threat and error management? Try to consider these before beginning the high workload phase of the flight.

We don’t know if this was the case in these three accidents, but it’s worth remembering that during flight, we pilots – and our passengers – experience the effects of gravity if our turns are steep.

In extreme cases, we experience reduced vision and ultimately a G-LOC – a gravity-induced loss of consciousness.

This is more likely to happen if you’re unfit, tired or fatigued, or not anticipating the possibility of G-LOC – often the case with any passengers – because you’re distracted by workload.

Almost as bad is reduced, or no, visual reference. Our body gyros ‘topple’ and our vestibular – inner ear – system lies to us about our physical orientation in space. This hampers our sense of direction and can cause additional physical stress.

Limitations of physical vision

In your PPL study, you learned how our vision allows threats and errors to present themselves.

Remember empty-field myopia? The eye tends to ‘rest’, focussing a few feet in front of us – nearer in poor visibility conditions – and that prevents us seeing obstacles further into the distance, but right in front of our aircraft.

For older pilots, adding to the problem of empty-field myopia, is that quality of vision is age-related. Generally, we become short-sighted as the years go by.

And if your aircraft windscreen is dirty, it makes the myopia even worse because your eyes will focus on spots immediately in front of you.

To overcome this, we need to ‘stretch’ our vision, allowing our focus to improve as we steadily look further and further into the distance.

For example, if you look out to the wing for a few seconds, then further down the wing, then beyond the wing, you’ll find your focus will sharpen.

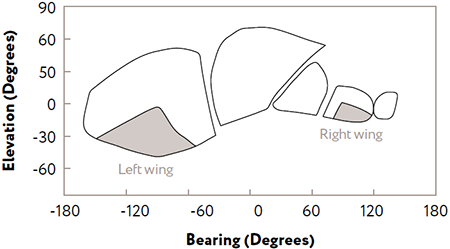

Difference between foveal and peripheral vision

Essentially, these two types of vision carry out different tasks to provide a 200-degree field of view (FOV) – although with varying levels of detail.

Foveal vision is the area of acuity – getting something in focus – directly in front of us. It’s a very narrow field and not as responsive to movement as our peripheral vision.

Peripheral vision is sensitive to stimulation, meaning items – aircraft – that don’t appear to move are often undetected.

Try holding a finger out to each side of your peripheral vision. If you move them, they’re visible, but if you keep your fingers still, eventually they become less obvious or even undetectable as they merge into the horizon.

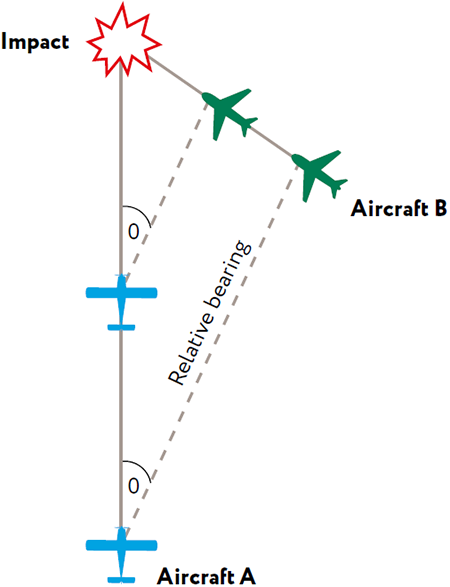

The interaction between foveal and peripheral vision has contributed to mid-air collisions – particularly through something called the ‘constant relative angle of convergence’. This is where an object in the peripheral range remains in the same relative position.

Lack of relative motion on collision course

Source: ATSB 'Limitations of the see-and-avoid principle' 1991

This is what happened in a mid-air collision in New Zealand in the late 1980s between two scenic aircraft at Milford Sound, and again in 2019, in an accident in the city of Ketchikan, in Alaska.

Knowing and recognising the strengths and weaknesses of these two forms of vision is vital to better understand how to look out effectively.

Other limitations to a good lookout

During training and type ratings, we often talk about the fact that design features of an aircraft can inhibit good views and limit visibility.

Windscreen pillars, wing configurations, and seating position can all have a significant effect on the ability of the pilot and their passengers to scan the horizon.

Some aircraft have sunshades, or shading printed into the windscreen. These are great for knocking back sun glare, but they can create an obstacle to good vision, especially when an angle of bank is applied.

Be aware it diminishes usable windscreen as you look into the turn. You may need to move to look around them or, if possible, lift the shade up.

Newer technologies such as ADS-B, can, ironically, affect our situational awareness. We pilots should integrate our visual and tech scans for the best situational awareness. But many pilots become so entranced with the bells and whistles, they literally lose sight of what’s actually happening outside their aircraft.

And the tech can fail. In the Ketchikan accident, the ADS-B in one machine was not broadcasting pressure altitude – necessary to provide an alert to the kit being used by the second pilot.

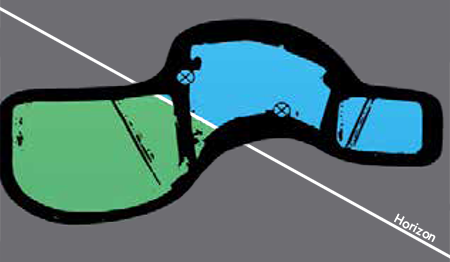

Using the horizon to improve lookout

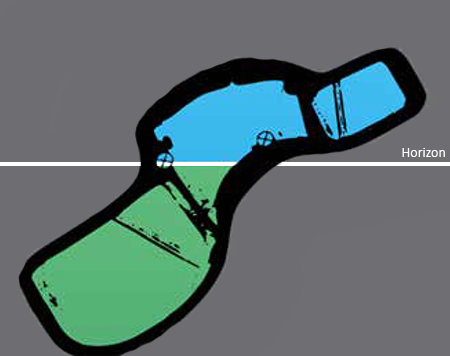

Let’s refer to the image below, often used for perspective, and reference to the horizon, in medium and steep turn lessons.

Photo: CAA/Marc Brogan

The image depicts the left-hand turn with the pilot sitting upright in the aircraft – their horizon is angled.

This means a natural movement of the head is down the turn rather than across the horizon, which should be your reference for VFR flight for yourself, and other aircraft.

If you slightly lean away from the turn, the horizon assumes a level perspective, and the scan now has a greater FOV around to the left, where the aircraft is turning.

This is important to understand because we actually see the world like this image below.

Limited cockpit visibility from a typical general aviation aircraft

Source: ATSB “Limitations of the see-and-avoid principle” 1991

As you can see, the actual usable FOV – when you allow for aircraft design and our human eyeballs – is extremely limited. If you were to overlay this on to a real-world image – diagrammatically presented below – the picture becomes obvious.

Pilot forward view, without tilting their head

Source: CAA

By leaning slightly away from the turn, your head can now be moved, with a greater reference to the actual horizon, past aircraft design features that may otherwise limit the view and your peripheral vision.

You’re now more effectively able to look into the actual plane of movement and the reference for all other pilots, the horizon.

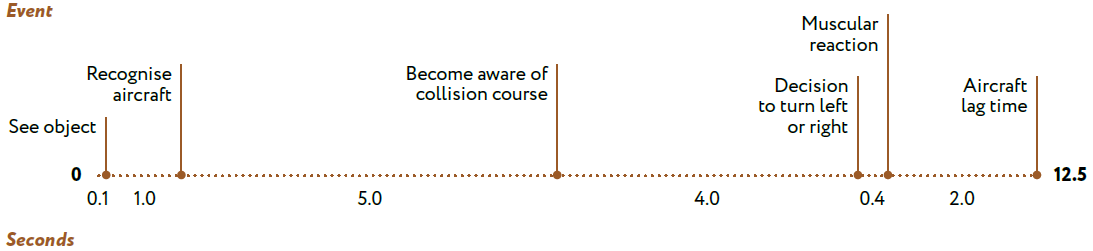

Aircraft identification and reaction time

Source: FAA AC 90-48D CHG 1 Pilots’ role in collision avoidance

The picture below simulates that change of view, as does the second diagram.

Photo: CAA/Marc Brogan

Pilot forward view, tilting their head so they have a wider FOV

Source: CAA

An effective scan

The timeline above shows the number of seconds you have to react to a collision threat.

Become acquainted with the principles of an efficient VFR scan so that it becomes automatic. Check out the material at the links under more information below.

Having to do an effective VFR scan is often accompanied by the stress of undergoing a flight check, flying a new aircraft, learning a lesson, starting a new job, flying on a particularly hot or cold day, all the while trying to move around in a confined space to get a good look at what’s where outside.

If you follow the principles of an effective scan as a matter of course, it will free up ‘brain space’ to accommodate these other pressures.

How many of the factors in the accidents described here are present every day in your flying? Hot day? Radio clutter? Coming into land at an unattended airfield?

Consider your place in the air. We pilots are the greatest weakness in the aviation loop. But we can also be the last slice of swiss cheese preventing a catastrophe.

Work Together, Stay Apart

The number of critical near-miss incidents in unattended circuits has increased every year since 2016.

The CAA has launched the Work Together, Stay Apart campaign – an initiative highlighting the very real threats to all aircraft who fly in proximity to other machines and the pilots flying them.

The campaign is focusing on flying behaviours at unattended aerodromes, and standardising practices in their circuits.

Look out for the Summer 2023/24 issue of Vector, which will be wholly dedicated to education about this one problem.

More information

ATSB: See and Avoid(external link)

ATSB: Limitations of the See-and-Avoid Principle(external link)

Vector Online: So you think you can see and avoid

Situational awareness and threat and error management

NTSB: Ketchikan midair(external link)

Footnote

1 In a well-managed flight, the passengers will have been briefed, and that will include them looking out for other aircraft and informing the pilot. So they’re an important aid to lookout and situational awareness.