Instructional theory

Psychologists over the years have proposed various theories on learning, and from these we can gain an insight into the learning process. Listed below are some of the most widely accepted learning components, sometimes referred to as ‘Laws of learning’.

What is taught first, often creates a strong, almost unshakeable impression. Therefore what is taught, and what is learnt, must be right the first time. Un-teaching is more difficult than teaching.

The student learns best when they are ready to learn, motivated, and understand clearly the objectives for the lesson. Being ready to learn also entails consideration of Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs (see Human behaviour). A student distracted by fatigue, stress, home or relationship issues, etc, will not be ready to learn.

Individuals learn best when they see a reason for learning. If students have a clear objective, and a well defined reason for learning, they make rapid progress. You must explain the relevance of each lesson. For example, why must the student recognise the symptoms of the approaching stall? Where does this lesson fit with those covered previously, and those lessons ahead?

Those things most often repeated are best remembered6. Every time practice occurs, learning continues. Students do not learn crosswind landings from one instructional flight. You must provide opportunities for practice and must see that this process is directed toward a goal.

"One of the most powerful forms of reward available to the instructor is praise"7. Learning is strengthened when accompanied by a pleasant or satisfying feeling and weakened when associated with an unpleasant one. Termed the 'Law of effect', it is based on the emotional reaction of the learner. An experience that produces feelings of defeat, frustration, anger, confusion or futility is unpleasant for the student. If, for example, an instructor attempts to teach landings during the first flight, the student is likely to feel overwhelmed. Impressing the student with a difficult manoeuvre can make the later teaching task difficult. It is better to tell students that a manoeuvre or problem, although difficult, is within their capabilities to perform or understand. Whatever the learning situation, it should affect the student positively and give them a feeling of satisfaction.

A vivid, dramatic or exciting learning experience teaches more than does a routine or boring experience. This implies that the student will learn more from the real thing. In contrast to in-flight instruction, the classroom limits the amount of realism that can be brought into the teaching. Instructors should use imagination in the briefing. Photographs, mock-ups, and audio-visual aids can add vividness to classroom instruction.

The things most recently learned are best remembered. Instructors recognise recency when they carefully plan a summary of their pre-flight briefing or post-flight critique. You must repeat, restate or re-emphasise important points at the end of the lesson.

Feedback on knowledge, skills and attitudes as learning takes place is important guidance for assessment on performance and progress. This feedback should be linked to the objectives of the lesson and focused on steps to take for next lesson or for improvement. It should guide the student in developing their own ‘self-reflection’ skills for assessing their own performance when flying solo.

One view of learning that is of particular importance to the flight instructor, is that proposed by MS Knowles36 on how adults should be treated differently from children, based on their psychological differences.

As flight instructors deal with adult or early adult education, how these differences affect adult learning is of some importance.

For a fuller explanation of how these factors affect the adult learner, flight instructors are encouraged to read The Adult Learner: A Neglected 5pecies36 by MS Knowles (1988), Chapter 3.

Initially, all learning comes from perceptions that are directed to the brain by one or more of the five senses. Psychologists have determined that normal individuals acquire about 75 percent of their knowledge through the sense of sight, 13 percent through hearing, 6 percent through touch, 3 percent through smell and 3 percent through taste. They have found that learning occurs most rapidly when information is received through more than one sense.

Perception involves more than receiving stimuli from the five senses. Perceptions result when a person gives meaning to sensations. People base their actions on the way they believe things to be, and this will depend on many factors within each person8. The experienced flight instructor, for example, will interpret engine rough running quite differently to an inexperienced student. Because perceptions are the basis of all learning, some of the factors that affect the perceptual process are discussed below.

Every experience and sensation that is funnelled into the brain is coloured by the individual's own beliefs and value structure. Spectators at a rugby game may 'see' an infraction or foul differently depending on which team they support. The precise kinds of commitments and philosophical outlooks that the student holds are important for you to know, since this knowledge will assist in predicting how the student will interpret experiences and instructions. For example, the student with an interest in crop-dusting will perceive instruction differently from those interested in airlines or helicopters. Motivation is also a product of a person's value structure; those things most highly valued are pursued while those of less importance are not.

A student's self-image, described as 'confident' or 'insecure' has a great influence on the perception process. How a person sees themselves is a powerful factor in learning. The student who attributes success to hard work, and failure to lack of effort, will perform better than a student who attributes success to luck and failure to lack of ability9.

Learning depends on previous perceptions (experience) and the availability of time to relate new perceptions to the old. Therefore sequence and time available affect learning1. A student could probably stall an aircraft on the first attempt, regardless of previous experience. But the stall cannot be really learned unless some experience in normal flight has been acquired. Even with such previous experience, time and practice are needed to relate the new sensations and experiences associated with stalls in order to develop a perception of the stall. The length and frequency of an experience affect the learning rate. The training syllabus must provide time and opportunity. As a general guide for ab initio flight instruction little and often is best10.

Fear adversely affects a student's perception by narrowing their perceptual field. The field of vision is reduced, for example, when an individual is frightened and all perceptual faculties are focused on the thing that has generated fear. Anxiety or worry (milder forms of fear) take up processing space in the working memory and may produce a "deficit in memory"11, for example, during the initial practice of steep turns, a student may focus attention on the altimeter and completely disregard outside visual references. Anything an instructor does that is interpreted as threatening makes the student less able to accept the experience you are trying to provide. It adversely affects all the student's physical, emotional and mental faculties. Hence the extensive use, in flight instruction, of the follow-me-through exercise.

The student gains perception from the feel of control inputs but more importantly in the early stages, the student gains from the elimination of fear. You need to build a climate of confidence in which the student realises that you will not allow them to put the aircraft into a dangerous situation, and so the student's confidence in performing the manoeuvre grows. Learning is primarily a psychological process. As long as the student feels capable of coping with a situation, each new experience is viewed as a challenge.

Teaching is consistently effective only when those factors that influence perceptions are recognised and taken into account.

Insights involve the grouping of perceptions into meaningful wholes. To ensure that these occur, it is essential to help the student realise the way each piece relates to all the other pieces of the total pattern of the task to be learned8.

As an example, in straight-and-level flight, in an aircraft with a fixed-pitch propeller, the RPM will increase when the throttle is opened and decrease when it is closed. RPM changes, however, can also result from changes in pitch attitude without changes in power setting.

Therefore engine RPM, power setting, airspeed and attitude are inter-related. Understanding the way in which each of these factors may affect all of the others, and understanding the way in which a change in any one of them may affect changes in all of the others, is imperative to true learning. This mental relating and grouping of associated perceptions is called insight.

Insights will almost always occur eventually, whether or not instruction is provided. Instruction, however, speeds this learning process by teaching the relationship of perceptions as they occur, thus promoting the development of insights by the student.

It is a major responsibility of the instructor to organise demonstrations, explanations and student practice so that the learner has the opportunity to understand the inter-relationship of experiences.

Pointing out the relationships as they occur, providing a secure and non-threatening environment in which to learn, and helping the student acquire and maintain a favourable self-concept are most important in the learning process.

Motivation is the dominant force that governs the student's progress and ability to learn12. Motivations may be negative or positive, tangible or intangible, or subtle or obvious.

Negative motivations are those which engender fear. They are not characteristically effective in promoting efficient learning.

Positive motivations are provided by the promise or achievement of rewards. These rewards may be personal or social; they may involve financial gain, satisfaction of the self-concept, or public recognition. Some motivations that can be used to advantage by you include the desire for personal gain, the desire for personal security, the gaining of a sense of achievement, the desire for group approval, and the achievement of a favourable self-image.

The desire for personal gain, either the acquisition of things or position, is a basic motivation for all human endeavours. An individual may be motivated to dig a ditch or to design an aircraft solely by the desire for financial gain.

Students are like all other workers in wanting a tangible return for their efforts. If such motivation is to be effective, they must believe that their efforts will be suitably rewarded. These rewards must be constantly apparent to the student during instruction, whether they are to be financial, self interest or public recognition.

The student may not appreciate why they are learning a particular lesson. If motivation is to be maintained it is important that you ensure the student is aware of the applications of the lesson. This is usually achieved through the verbal introduction to the pre-flight brief. The attractive features of the activity to be learned can provide a powerful motivation. Students are anxious to learn skills that may be used, and if they can be made to understand how each learning task relates to their goals, they will be eager to pursue it.

The desire for personal comfort and security is a motivation that is often inadequately appreciated by instructors. All students want secure, pleasant conditions and states of being. If they recognise that what they are learning may promote this objective, their interest is easier to attract and hold. Insecure and unpleasant training situations retard learning.

Everyone wants to avoid pain and injury. Students are likely to learn actions and operations that they realise may prevent injury. This is especially true when the student knows that the ability to act correctly in an emergency results from adequate learning.

Group approval is a strong motivating force. Every person wants approval of friends and superiors13. Interest can be stimulated and maintained by building on this natural force. Most students enjoy the feeling of belonging to a group and are interested in attaining prestige among their fellow students.

Every person seeks to establish a favourable self-image. This motivation can best be fostered by you through the introduction of perceptions which are based on facts previously learned and which are easily recognised by the student as achievements in learning. This process builds confidence, and motivation is strengthened as a result.

Positive motivation is essential to learning. Negative motivations in the form of reproof and threats should be avoided with all but the most overconfident and impulsive students.

Slumps in learning are often due to slumps in motivation. Motivation does not remain at a uniform level and may be affected by outside influences, such as physical fitness or inadequate instruction. You must tailor instruction to maintain the highest possible level of motivation and should be alert to detect and counter lapses in motivation.

While the flight instructor must consider the motivation of students, it is also essential for the professional flight instructor to consider their own motivation. "The potential influence of an instructor is so great that it merits a career path and status" of its own, while "the use of flight instruction as a transient position to accumulate the hours needed to progress to an airline position is a hackneyed strategy and an unfortunate syndrome for the industry"14.

Learning may be accomplished at any of several levels. From the lowest to progressively higher levels of learning, these are:

For example, a flight instructor may tell a beginning student pilot to enter a turn by banking the aircraft with aileron and applying sufficient rudder in the same direction to prevent slip or skid. A student who can repeat these instructions has learned by rote. This will not be very useful to the student if there is no opportunity to make a turn in flight (application) or if the student has no knowledge of the function of the aircraft controls (correlation).

Through instruction on the effect and use of the flight controls and experience in their use in straight-and-level flight, the student can develop these old and new perceptions into an insight on how to make a turn. At this point the student has developed an understanding of the procedure for turning the aircraft in flight. This understanding is basic to effective learning but may not necessarily enable the student to make a correct turn on the first attempt.

When the student understands the procedure for entering a turn, and has practised turns until an acceptable level of performance can be consistently demonstrated, the student has developed the skill to apply what has been taught.

Further understanding of the associated concepts are covered in the instructional techniques course syllabus when considering Bloom’s Taxonomy for Cognitive (head), Psycho-motor (hands), and Affective (heart) Domains.

Even though the process of learning has many aspects, the purpose of instruction is usually to learn a concept or skill. The process of learning a skill appears to be much the same whether it is a motor (physical) or mental skill. To provide an illustration of motor learning, follow the directions below:

In the learning task just completed, several principles of motor learning are involved and are discussed below.

The above exercise contains a practical example of the multifaceted character of learning. It should be obvious that, while a muscular sequence was being learned, other things were happening as well. The perception changed as the sequence became easier. Concepts of how to perform the skill were developed and attitudes were changed1.

Where there is a desire to learn, rapid progress in improving the skill will normally occur1. Conversely, where the desire to learn or improve is missing, little progress is made. In the exercise above, it is unlikely that any improvement occurred unless there was a clear intention to improve. To improve, one must not only recognise mistakes, but also make an effort to correct them. The person who lacks the desire to improve is not likely to make the effort and consequently will continue to practise errors.

The best way to prepare the student to perform a task is to provide a clear, step-by-step example1. Therefore all exercises start with a demonstration. The demonstration is another way of stating the lesson objective – here is what you (the student) will be able to do at the end of this lesson. The demonstration is followed with a step-by-step follow-me-through example.

Since you have now experienced writing a word with the wrong hand, consider how difficult it would be to tell someone else how to do it. Demonstrating how to do it will not result in a person learning the skill. Obviously practice is necessary1. As the student gains proficiency in a skill, verbal instructions mean more. Whereas a long detailed explanation is confusing to the student during early practice, comments are more meaningful and useful after the skill has been partially mastered.

In learning some simple skills, students can discover their own errors quite easily. In learning others, such as complex flight manoeuvres, mistakes are not always apparent. Or the learner may know something is wrong but not know how to correct it. In either case, you provide a helpful and often critical function in making certain that the student is aware of their progress. They should be told as soon after the performance as possible1, for they should not be allowed to practise mistakes. It is more difficult to un-learn a mistake and then learn it correctly, than it is to learn correctly in the first place. It is also important for students to know when they are right.

The experience of learning to write with the wrong hand probably confirmed what has been consistently demonstrated in laboratory experiments on skill learning. The first trials are slow and coordination is lacking. Mistakes are frequent, but each trial provides clues for improvement in subsequent trials. The learner modifies different aspects of the skill, how to hold the pencil, how to execute finger and hand movements. Skill learning usually follows the same pattern15.

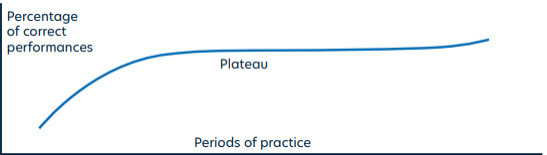

Figure 2 Typical progress pattern

The graph above shows a typical progress pattern. There is rapid improvement in the early trials, then the curve levels off and may stay level for significant periods of effort. Further improvement may seem unlikely. Such a development is a learning plateau, and it may signify any of a number of conditions. The learner may have reached capability limits, may be consolidating a level of skill, may have their interest wane, or may need a more efficient method for increasing progress. Keep in mind that the apparent lack of increasing proficiency does not necessarily mean that learning has ceased16. In learning motor skills, a levelling off process or plateau is normal and should be expected after an initial period of rapid improvement. This situation may cause impatience in the student. To avert discouragement, you should prepare them for this situation.

In planning for student performance, a primary consideration is the length of time devoted to practice. A beginning student reaches a point where additional practice is not only unproductive but may be harmful. When this point is reached, errors increase and motivation declines. The skilful instructor ends the learning experience before this point is reached. As a guide, when the basics of the manoeuvre have been achieved, it's time to end the lesson. For example, in the initial basic stall, when the student performs the actions of control column forward centrally and then full power, the basics of the manoeuvre have been achieved. It is for future lessons to build on this success, ie, aiming for coordination of control column and power, keeping straight and minimising height loss. As a student gains experience, longer periods of practice are profitable.

If an instructor were to evaluate the fifteenth writing of the word learning, only limited help could be given toward further improvement. You could judge whether the written word was legible, evaluate it against some standard, or perhaps assign it a grade. None of these would be very useful to a beginning student. The student could profit, however, by having someone watch the performance and critique it constructively to help eliminate errors. In the initial stages, practical suggestions are more valuable to the student than a grade.

As the instructor will not always be in the aircraft to give a judgement, self critique should be encouraged as a learning goal for the student.

"Research on motor skill learning has provided evidence for using mental practice"1. If you were to visualise yourself raising an arm out to the side, it would be possible to monitor activity in the deltoid muscles even though no physical movement had occurred. Imagery therefore has the effect of priming the appropriate muscles for subsequent physical action. The messages passed to the brain by the muscular system during visualisation are also retained in the memory. This means that physical skills can be improved even when they are only practised in the mind. The use of handouts and questionnaires on completion of the lesson can aid the student in reliving the experience in their mind.

The final and critical problem is use. Can the student use what has been learned? Two conditions must be present:

Transfer of learning is concerned with how well the learned material is applied in actual situations. For example, the student may have learned the symptoms of the approaching basic stall and the recovery technique. But are these symptoms recognised and acted on when observed in a turn?

Transfer cannot occur if the knowledge itself has not been initially mastered.

This points to a need to know a student's past experience and what has already been learned. In lesson planning, instructors should plan for transfer by organising lesson material to build on what the student already knows. Also, each lesson should prepare the student to learn what is to follow.

Flight instructors are encouraged to read Essentials of Learning for Instruction1 by RM Gagne and MP Driscoll (2nd ed) (1988).

Why people forget may point the way to helping them remember.

A person forgets those things that are not used. But the explanation is not that simple. Experimental studies show, for example, that a hypnotised person can describe specific details of an event that would normally be beyond recall. Apparently the memory is there, locked in the recesses of the mind. The difficulty is summoning it up to consciousness8.

From experiments, two conclusions about interference can be drawn:

Repression is the submersion of ideas into the unconscious mind. Material that is unpleasant or produces anxiety may be treated this way, but not intentionally. It is subconscious and protective. This type of forgetting is rare in aviation instruction.

When a person forgets something it is not lost; rather it is unavailable for recall. Hunt and Poltrock offer the analogy of books in a library that are never removed from the shelves, whereas the index cards may be lost. Your problem then, is how to make certain that the student's learning is always available for recall. The following suggestions can help.

Teach thoroughly and with relevance. Material thoroughly learned is highly resistant to forgetting. Meaningful learning builds patterns of relationships in the student's consciousness. Whereas rote learning is superficial and is not easily retained, meaningful learning goes deep because it involves principles and concepts anchored in the student's own experience.

Long-term memory is enhanced if information is well encoded, put into several different files by being explained in different ways and thus well cross-indexed (association). Retention can be assisted by stimulation of interest.

The following are five significant principles that are generally accepted as having a direct application to remembering:

Responses that give a pleasurable return tend to be repeated. Absence of praise or recognition makes recall less likely.

Each bit of information or action, which is associated with something already known by the student, tends to facilitate later recall.

People learn and remember only what they wish to know. Without motivation there is little chance for recall. The most effective motivations are internal, based on positive or rewarding objectives.

Although we generally receive what we learn through the eyes and ears, other senses also contribute to most perceptions. When several senses respond together, fuller understanding and a greater chance of recall is achieved.

Each repetition gives the student an opportunity to gain a clearer and more accurate perception of the subject to be learned, but mere repetition does not guarantee retention. Practice gives an opportunity for learning but does not cause it. Three or four repetitions provide the maximum effect, after which the rate of learning and probability of retention fall off rapidly.