Instructional theory

By definition, learning is - a change of behaviour resulting from experience that persists. To successfully accomplish the task of helping to bring about this change, you must know why human beings act the way they do. Knowledge of basic human needs and defence mechanisms will aid you in organising student activities and in promoting a climate conducive to learning.

The relationship between you and the student has a profound impact on how much, and what, the student learns. Consider your own experiences with your first flight instructor. You probably thought your instructor was the best, and you probably strove to emulate and please your instructor. The power and impact of role modelling must not be underestimated. The instructor directs and controls the student's behaviour, guiding them toward their goals, by creating an environment that enables the student to help themselves.

To students, the instructor is a role model, a symbol of authority. Students expect you to exercise certain controls, and they recognise and submit to authority as a valid means of control. The controls the instructor exercises – how much – how far – to what degree – should be based on generalisations of motivated human nature.

Your ingenuity must be used in discovering how to realise the potential of the student. The responsibility rests squarely on you. If the student is perceived as lazy, indifferent, unresponsive, uncooperative or antagonistic, the cause may lie in your methods of control. The raw material is there, and the shaping and directing of it lies in the hands of those who have the responsibility of controlling it.

A productive relationship with the student depends on your knowledge of students, as human beings and of the needs, drives and desires they continually try to satisfy in one way or another.

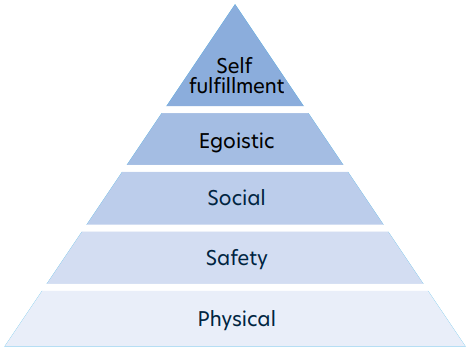

The needs of students, and of all humans, are given labels by psychologists and are generally organised in a series of levels. The 'pyramid of human needs' has been suggested by Abraham Maslow.

Figure 1 Maslow's hierarchy of needs

Individuals are first concerned with their need for food, rest, exercise and protection from the elements. Until these needs are satisfied to a reasonable degree, they cannot concentrate on learning or self-expression.

Once a need is satisfied, it no longer provides motivation. Therefore each individual strives to satisfy the needs of the next higher level.

Protection from danger, threat or deprivation are called safety or security needs. These needs, as perceived by the student, are real and will affect student behaviour.

If individuals are physically comfortable and have no fear for their safety, their social needs then become the prime influence on their behaviour. These needs are to belong, to associate, and to give and receive friendship and love. Many studies have demonstrated that a tightly knit, cohesive group, under proper conditions, will be more effective than an equal number of separate individuals. As students are usually separated from normal surroundings, their need for association and for belonging will be more pronounced.

The egoistic needs will usually have a direct influence on the student-instructor relationship. These needs are two kinds:

At the apex of the hierarchy of human needs are those for self-fulfilment, for realising your own potential, for continued development, and for being creative in the broadest sense. This need of a student should offer the greatest challenge to you. Aiding another in realising self- fulfilment is probably the most worthwhile accomplishment an instructor can achieve.

Certain behaviour patterns are called defence mechanisms because they are subconscious defences against unpleasant situations. People use defences to soften feelings of failure, to alleviate feelings of guilt, and to protect feelings of personal worth and adequacy.

Although defence mechanisms can serve a useful purpose, they can also be hindrances. Because they involve some self-deception and distortion of reality, defence mechanisms do not solve problems. They alleviate symptoms, not causes. Common defence mechanisms are rationalisation, flight, aggression and resignation.

If students cannot accept the real reasons for their behaviour, they may rationalise. This device permits them to substitute excuses for reasons. In addition, they can make those excuses plausible and acceptable to themselves. Rationalisation is a subconscious technique for justifying actions that otherwise would be unacceptable.

Students often escape from frustrating situations by fleeing, either physically or mentally. To flee physically, students may develop ailments that give them satisfactory excuses for removing themselves from frustration. More frequent is mental fleeing through daydreaming. Mental fleeing provides a simple and satisfying escape from problems. If students get sufficient satisfaction from daydreaming they may stop trying to achieve their goals.

Everyone gets angry. Anger is a normal, universal human emotion. In a briefing room, classroom or aircraft, extreme anger is relatively infrequent. Because of social strictures, student aggression is usually subtle. Students may ask irrelevant questions or refuse to participate in class activities.

Students may become so frustrated that they lose interest and give up. The most common cause of this takes place when, after completing the early phase of a course without grasping the fundamentals, a student becomes bewildered and lost in the advanced phase. From that point learning is negligible, although the student may go through the motions of participating.

To minimise student frustration and achieve good human relations are basic instructor responsibilities.

Students gain most from wanting to learn rather than being forced to learn. Often students do not realise how a particular lesson or course can help them reach an important goal. Each lesson must have relevance. When they can see the benefits or purpose of a lesson or course, their enjoyment and their efforts will increase.

Students feel insecure when they do not know what is expected of them or what is going to happen to them. For example, consider your own feelings before your first basic stall lesson.

Instructors can minimise such feelings of insecurity by telling students what is expected of them and what they can expect, not just the control inputs to use.

When instructors limit their thinking to a group without considering the individuals who make up that group, their effort is directed at an average personality which really fits no one18. After giving the same lesson several times, it is easy for you to overlook this aspect.

Each individual has a personality which is unique and which should be constantly considered.

When students do well, they wish their abilities and efforts to be noticed. Otherwise they become frustrated. Praise from you is usually ample reward and provides incentive to do even better. Praise given too freely, however, becomes valueless.

Although it's important to give praise and credit when deserved, it's equally (not more) important to identify mistakes and failures. However, to tell students that they have made errors and not provide explanations does not help them. Errors cannot be corrected if they are not identified, and if they are not identified they will probably be perpetuated through faulty practice. If the student is briefed on the errors made, and is told and shown how to correct them, progress and accomplishment can be made.

Students want to please their instructor. Therefore, students have a keen interest in knowing what is required to please you. If the same thing is acceptable one day and not the next, the student becomes confused. Your philosophy and actions must be consistent. This often leads to a desire by the student to fly with only one instructor.

No one, including the students, expects an instructor to be perfect. You can win the respect of students by honestly acknowledging mistakes. If you try to cover up or bluff, the students will often sense it. Such behaviour destroys student confidence in you. If in doubt about some point, you should admit it. You should report back to the student after seeking advice from the supervising instructor, CFI, or recognised texts.

Good human relations promote effective learning.